- Home

- Christian Day

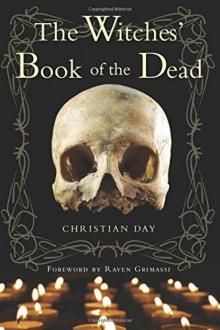

The Witches' Book of the Dead

The Witches' Book of the Dead Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

A Note About the Author and Translator

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

Farrar, Straus and Giroux ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on Christian Kracht, click here.

For email updates on Daniel Bowles, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Frauke and for Hope

What is life? Thats the question. Something not necessarily leading to a plot.

—VIRGINIA WOOLF

I have only this one heart, no one can know it but me.

—JUN’ICHIRŌ TANIZAKI

PART ONE

序

1.

There hadn’t been a rainier May in Tokyo for decades; the smudgy grayness streaking the overcast sky had been dimming to a deep, deep indigo day after day; hardly anyone could recall such cataclysmic quantities of water. Hats, coats, kimonos, uniforms had become shapeless and ill-fitting; book leaves, documents, scrolls, maps began to warp. There, a wayward, imprudent butterfly was struck down in midflight by rainstorms, down to the asphalt, whose water-filled depressions tenaciously reflected the luminous neon signs and paper lamps of restaurants at night: artificial light, cleaved and divided up by the arrhythmic pelting of endless downpours.

A handsome young officer had committed some transgression or other, and he now intended to punish himself in the living room of an altogether nondescript house in the western part of the city.

The lens of the camera was inserted into a corresponding aperture in the wall of the adjoining room, the hole’s edges insulated with strips of fabric so that the humming of the apparatus might not disturb the delicate scene within. Kneeling down, the officer opened his white jacket left and right, and with almost imperceptibly trembling yet precisely searching fingertips, he located the correct spot and leaned forward, grasping for the wispy-sharp tantō lying before him on a sandalwood block.

He paused, listening, hoping to hear once more the sound of the falling rain, but there was merely a quiet and mechanical whirring behind the wall.

Immediately after the brightly polished tip of the dagger had pierced the bellywrap and the fine white skin of the abdomen underneath, its gentle concavity encircled by only a few black hairs, the blade slid through the soft tissue into the man’s innards—and a fountain of gore sprayed sideways toward the exquisite calligraphy of the kakejiku.

It looked as if the cherry-red blood had been intentionally spattered by an artist who had shaken out his brush with a single, whiplike motion of his wrist across the scroll hanging there in the alcove in delicate simplicity.

Grunting with pain, the dying man slumped over, nearly losing consciousness, and then with tremendous effort righted himself again. Erect, he drew the knife now lodged in him across his body laterally, from left to right, and then he looked up, past the hole through which the camera was filming him; at length, he spat blood thickened to a glistening gelatinous mass, and his eyes grew dim and vacant. Arrangements had been made to leave the camera running.

After the film had been developed, a copy of it, sealed in oily cellophane, was carried carefully through the rain. The last streetcars ran around eleven o’clock in the evening. One had taken pains to deliver the print punctiliously and on time.

2.

The film director Emil Nägeli, from Bern, sat uncomfortably upright inside the rattletrap metal fuselage of an airplane, biting and tearing at his fingertips. It was spring. How his brow became moist, how he rolled his eyes in nervous tension—believing he could sense the approach of an imminent disaster—how he sucked and gnawed. And while his skin grew sore and red from the pressure of his teeth, he envisioned time and again that the plane would suddenly burst apart in the sky with a flash of light.

It was dreadful; he was at the end of his tether. Polishing his round spectacle lenses, he stood up to visit the lavatory—but raising the toilet lid, to his horror, he was able to see down and out through the hole into the emptiness below, so he returned to his seat in the cabin, drumming the cover page of a glossy magazine with his marred fingertips and eventually asking for a drink that never arrived.

Nägeli was traveling from Zurich to the new Berlin, the spleen of that insecure, unstable nation of Germans. Beneath him the dappled forests of the Thurgau drifted by—for a time the glinting of Lake Constance was visible—and then he espied down below the secluded, desolate villages of a Frankish lowland beset by shadows. The airplane took him ever northward, beyond Dresden, until shapeless clouds once more obscured his view.

Soon they made their tinny, turbulent descent—for some reason he was informed that the plane was to undergo repairs at Berlin’s Central Airport; apparently something in the propeller housing was defective. He wiped his clammy forehead with the end of his tie. And then, finally, with apologies, he was served a cup of coffee. Hardly sipping it, he looked out the window into the fathomless white.

His father had died a year ago. All of a sudden, as if his father’s passing had perhaps been an initial sign of his own mortality, middle age had set in, unnoticed, overnight, with all its prudishly concealed, secretly suffered mawkishness, its perennial purple self-pity. Now all that would follow was old age, an era of feebleness, and nothing more thereafter but a void that to Nägeli seemed wholly grotesque, which is why he worried at his fingers, the skin of which had now peeled away in milky, translucent little shreds.

At home in Switzerland he had often dreamed of stepping out into his snow-covered garden in winter, stripped naked, of leaning over to perform some breathing exercises and knee bends, and of observing the ravens circling overhead in search of sustenance amid the snow. They glided gracefully beneath leaden skies, without any consciousness of themselves. He would notice neither the numbing cold on his bare feet, nor the crystalline-whirling snowdrifts, nor the tearlet that fell forth into the frost.

Someone would shout Cut! and an assistant would prepare a close-up of the tear and approach the actor with a pipette. Nägeli would persist in his squat, holding his pose. At the same time, he would open his eyes widely so he could cry naturally with greater ease should the artificial tear, as was often the case, seem too theatrical.

At that instant Nägeli would become aware of standing both before and behind the camera, and he would feel a malignant, disturbing shudder at this disjointedness, and it was then that he would usually awake.

Emil Nägeli was a rather likeable man; in conversation he would frequently lean forward slightly; he would display great civility that never seemed contrived; blond, soft, yet somewhat stern eyebrows gave way to a pointy Swiss nose; he was sensitive and alert, as if his nerves extended beyond his skin, and consequently was quick to blush; he harbored a healthy skepticism of the entrenched worldviews of others; above his weak chin were set the supple lips of a sulking child; he wore subtly patterned English suits of dark-brown wool whose somewhat abbreviated trouser legs ended in cuffs; he liked to smoke cigarettes, now and then a pipe, and was not a drinker; from watery blue eyes he gazed into a sorrowful and wondrous world.

He pretended to like eating hard-boiled eggs with coarse bread and butt

er and slices of tomato more than anything else, but in truth he intensely disliked the process of consuming food, which bored and, indeed, occasionally repulsed him. And thus, whenever by supper he had again ingested nothing but coffee, his friends tended to suffer from his unpleasant moods, brought on by his low blood-sugar levels.

Nägeli was losing his light-blond hair, on both his brow as well as his crown; he had begun combing a lengthy strand from his temple over his thus repudiated pate. To conceal the gradual, persistent slackening of his double chin, he had grown a full beard that, disappointed at the result, he had hastily shaven off again; those wrinkly dark-bluish rings under his eyes, which used to appear in the mirror only in the brightness of morning, now no longer faded over the course of the day; his sight, were he to remove his varied spectacles, grew more myopic by degrees, blurry haziness set in; and his full-moon-shaped belly, which stood in marked contrast to the rest of his slender frame, could no longer be sucked in rigorously enough to be made invisible. He began to sense an all-encompassing limpness, an attenuation of the body, a steadily accruing, dumbfounded melancholy in the face of death’s impertinence.

3.

Nägeli’s father had been a lithe, almost delicate man made somewhat smaller by life; his shirts were always of a certain preciousness, and the very spot at which his trim cuff had enveloped his wrist to reveal both his thin gold wristwatch and his slender hand, tinged with hair only on its side, filled young Emil with a vague, mute, yet almost sexual longing that his own hand might one day rest on the white tablecloth of a sophisticated Bernese restaurant with similar elegance, at once an expression of pantheresque power poised to strike and of genteel restraint.

It was the selfsame hand, his mother had later told him, that had often struck him in the face as a small boy when he had refused to eat his rather lumpy porridge: the very hand, therefore, that had also once flung the punch-bell egg cracker from the breakfast table, together with its egg, against the wall, such that the dismal utensil clattered metallically against the red tiles and the egg then burst, leaving a repellent orange yolk stain on the wall that was still visible, or at least vaguely perceptible there, for years after.

That hand, however, had often protectively reached for Nägeli’s own, too, whenever his father and he crossed the streets of Bern and the boy forgot to look left for the automobiles roaring toward them; that hand had then pulled him back onto the sidewalk to safety, it had reassured him, it had warmed him, it had shielded him with the caring touch he so longed for: this same hand he clutched, nearly half a century later, in the hospice room of the Lutheran clinic at Elfenstein, in the capital, and he felt shame at the affectation of this final intimacy.

But where was he supposed to focus his imawashii gaze? Up at the ceiling, where everything converged anyway, or straight ahead, over to the deathbed, onto the wooden strip bathed in an icy-green fluorescent light, where commemorative photographs or wishes for recovery might have been pinned?

Or, yes, of course, better to direct it down into the past, to wish soundlessly now, at last, without lament, that those stories would return, the stories he had been told, the ones with the black raven and the black dog, while Emil was rolled up cavernously in his father’s silver fox blanket, down at the foot of his parents’ bed, groping with his small hand for his father’s familiar thumb, for his father’s hand.

Philip was what his father had called him his whole life. For forty-five years he flung this cruelty at him, only poorly disguised as humor, as if he didn’t know his son’s name was Emil; no, as if he did not care to know. Philip, that unyielding, calm, oppressive call—emphasis on the first i—and then, whenever the danger of some such punishment, of this or that unpleasant task had been instilled in the child, in the adolescent, then would come the tender, curative call of Fee-dee-bus, this belittling familiar form of a name that was not even his.

As his father lay dying, when Nägeli saw him alive for the last time, in Elfenstein, he lifted him gently from the bed, sliding his arms under his back, not knowing whether he was even permitted to do so—but his father was on his deathbed, what authority could forbid him this? The good Doctor Nägeli was now quite as light as a sack of straw, with alarming wrinkles on his back and hindquarters, and covered in dark-blue spots with yellowish edges from being so long abed.

Still, his intimately familiar face, closer and sweeter to Emil than anything else (with its salt-and-pepper beard, which his father had grown on the beach in the summery freshness of Jutland, among the prickly Baltic pines, and then, to the child’s disappointment, had abruptly shaved off again, as his son one day would his own; and those two enigmatic blue dots, one on the left side, one on the right, like tattoos, between the ear and the cheek; and that scar, amateurishly sutured, in the little groove between the lower lip and chin), this face now resembled the leathery parchment hide of a hundred-year-old tortoise. The skin had been pulled back from around the ears by the approach of death, and he spoke sotto voce from behind ruinous, putrid, obsidian-colored teeth.

And as the wind blew outside the window in a constant eerie whistle, he asked Emil whether—on the quite obviously blank hospital wall behind him—someone might have noted down Arabic characters, yes, there, look, Philip, my son, and Philip hadn’t forgotten to do his military service, had he, and when was he finally going to be discharged from this miserable clinic where his son had had him detained for reasons he could not fathom, and, most important, was he, Philip, ready to perform an insignificant service for a dying old man, a final favor, so to speak, he really couldn’t deny him that now, could he?

Shuddering, he waved for Emil to come closer, quite close, so that his father’s lips were right against his ear. He chuckled that he had refused to have his teeth cleaned for some time now, and in the last year of his life had consumed nothing but chocolate and warm milk, which was why his oral cavity was festering away and now he needed to whisper something immensely important and definitive to his son.

Tightly squeezing Emil’s wrist, he said, yes, come even closer (Nägeli could now smell the old man’s musty, mandragoric breath, imagining preposterously that his black teeth were snapping at him as he drew his son closer, quite close, with this very last effort), and then a single, almost powerful hah resounded; he was still able to aspirate the sound of the letter H, loudly, before a beetle-like rattling issued from the cavern of his father’s throat, and he passed away, and Nägeli gently closed his opaque and now streaming eyes.

4.

His elbow propped on a pillow, Masahiko Amakasu lay at home in Tokyo in the large room next to the kitchen, poured himself a few fingers of whiskey, set a record of a Bach sonata on the phonograph, and watched not quite half of the film on his home projector.

He made it no further than the sequence in which the young man, out of whose belly the haft of the knife jutted so lewdly, spouted carnage. Amakasu could not bear to look at blood; such things were deeply repulsive. He felt himself paralyzed by this cinematographically recorded, dehumanized imago of the real.

The whole thing reminded him of a series of sepia-toned photographs from imperial China he had once briefly had in hand, in which one could see an unfortunate fellow being tormented with lingchi and sent to his death—the condemned, who during the torture directed his gaze ecstatically heavenward like Saint Sebastian, was being violated with razors; his skin had been flayed, his extremities, finger by finger, sliced off.

Appalled, Amakasu had dropped the pictures as quickly as if they had been coated in contact poison. There were certain things one must neither depict nor duplicate, events in which we became complicit by beholding their representation; that had been enough; no more.

Recently, owing to severely blurred vision, he had sought treatment from a physician friend of his who, after a thorough examination replete with finger-wagging, had diagnosed a fairly serious infection and, while still in the anteroom, plucked out several of his eyelashes with tweezers, causing almost unendurable pain; the prob

lematic lashes had apparently grown inward, toward the eyeball. While he could now focus his eyes very well again, the recollection of that procedure, which couldn’t have lasted more than a minute, triggered in him a profound discomfort similar to that produced by the filmic depiction of this suicide.

In recent weeks Amakasu had taken up watching dozens of European feature films: Murnau, Riefenstahl, Renoir, Dreyer. Die Windmühle by the Swiss director Emil Nägeli had also been among them, a simple story of an austere Swiss mountain village that recalled in its long-winded narrative style Ozu and Mizoguchi, and for Amakasu represented an attempt to define the transcendental, the spiritual—employing the tools of cinematic art, Nägeli had quite clearly succeeded in illustrating the sacred, the ineffable, within this very uneventfulness.

Occasionally Nägeli’s camera lingered long and gratuitously on a coal oven, a log, the braided circlets of hair on the back of a farm girl’s head, on her white nape dusted with blonde down, only then to glide fantastically out an open window toward the fir trees and snow-covered mountain heights as if incorporeal, as if the director’s camera were a floating spirit.

Amakasu had often dozed off while examining this Swiss film, uncertain whether this was for a few seconds or for whole minutes at a time; his head would flop to the side, and after feeling for a moment that he was flying or perhaps walking underwater, he would awake again with a frightened jolt; the film’s suspended, almost abstract mosaics, flickering in hues of gray, had blended with the images from his dreams and covered his consciousness with the violet sheen of an indeterminate fear.

Now, however, he had this repugnant suicide film before him, this documentation of a real and actual death. Shutting off the projector with a curt flick of the hand, Amakasu lit a cigarette, remained sitting in the humid breeze of the table fan, and considered just not sending the reel to Germany, but rather locking it away in the basement archive of the Ministry, leaving it there to be forgotten forever. Gradually, he thought, he was becoming the type of person who has lost all faith, except perhaps faith in the counterfeit.

The Witches' Book of the Dead

The Witches' Book of the Dead