- Home

- Christian Day

The Witches' Book of the Dead Page 3

The Witches' Book of the Dead Read online

Page 3

8.

These ceaseless thoughts of his dead father had clouded his mind in Paris. Dejectedly he left the city, marred for him once more by reading Flaubert, for Scandinavia. After the Madame Tussaud debacle he was to produce his first sound film for the Danish Nordisk studio, but Nägeli didn’t manage to shoot a single meter of film, and instead began to exorcise the whole disaster in his mind by way of ceaseless movement through space: by traveling around aimlessly.

All the while, not the slightest idea occurred to him; he bristled in his thoughts at the notion that the squawking of actors would henceforth interfere with the much more profound language of the visual, that the floating, lyrical motion of the camera would now be subject to the acoustic clumsiness of mediocre dialogue.

He spent a few weeks in Gotland, went for walks on the beach, met an old, prematurely aged friend, collected leaves, then journeyed up through the pallid rains of Sørlandet to meet Hamsun.

Nägeli had planned, on behalf of Nordisk, to discuss with the unapproachable, recalcitrant Norwegian a possible film adaptation of his novel Mysteries—Hamsun kept Nägeli waiting for hours on a wooden bench in front of his home, only apple slices and water set out, while upstairs in the house the Poet indulged in yogic contortions.

In those days Nägeli was hedged in by a constant, extended, gray sense of suspension; finally, his secretary sent him UFA’s invitation, formulated with Teutonic precision, to travel to Berlin, an invitation that reached him at the post office in Oslo. Hamsun, meanwhile, remained disinterested and dismissive. Nägeli took the train south again, toward Gothenburg, then to Malmö, and the weather remained bleak.

Having finally dozed off in the railroad car, he saw in a dream his father’s wrinkly neck, the dots of his medical tattoos, the pallor of his kind face covered in age spots, his silvered hair spilling down a nape furrowed like the crevices in a wasteland, his intensely pale-blue, slightly oblique Kyrgyz eyes, and finally, much later, the death mask on the wall of the hospital room, over in the alcove, and the shadows of the Swiss birch trees sweeping gently over it.

9.

Masahiko Amakasu’s childhood, in his receding memory as dull and lackluster as a winter’s sky, had been that of a precocious, peculiar boy who at not yet three years of age read the newspaper aloud to his parents, a boy who gushed theatrically—he had now barely turned five—about precisely elaborated, sublimely nuanced suicidal fantasies, and in his parents’ garden at night secretly excavated pits underneath the gorse bushes to hide his considerable collection of violent picture books, the possession of which had been forbidden him under threat of severe beatings.

Masahiko was sent off to boarding school early, too early, of course; he had not reckoned with the fact that his parents, who had always seemed so liberal, modern, and educated, would commit him to one of the Empire’s most merciless flogging parlors—though whether this had occurred out of ignorance or Mr. and Mrs. Amakasu were trying in some way to build his character he was never able to find out.

Their seeming open-mindedness was on shallow ground, however; his own grandmother had adhered so much to the old traditions that she had had her teeth lacquered black—even then already a vanished ideal of beauty.

Every year during the autumn holidays they would travel by railroad northeast to Hokkaidō to gather mushrooms and marvel at the glorious transformation of the foliage, the affirming, melancholy-tinged serenity to which both his father and his mother had looked forward all summer long.

No sooner had the family set up its picnic area (his mother carefully spreading out a snow-colored linen sheet and bedecking it with tankards, black-and-red lacquered boxes, and bottles of almond milk and beer, while above them the leaves of maple trees, larches, and beeches shimmered in a hundred thousand ecstatic shades of color) than young Masahiko liked to disappear behind some tree, allegedly to play, in order to picture to himself there in great detail, after successfully liberating his hiding place from insects fumbling about, the spectacle of his own funeral.

In it his mother, quite openly wailing, would sit before his urn, as would his father, reproaching himself extravagantly in soft silence while gnawing off the insides of his cheeks, and even his classmates, those who had hung him up, the undersized and almost pathologically quiet Masahiko, on a coat hook by the elastic band of his underwear every morning for several weeks before their geography lesson, even they would stand there mute in their navy-blue school uniforms, somewhat off to the side, intimidated by the nearness of death, while the sun raged intermittently through the leaves above.

One of his teachers would step forward, slender, infirm, and bespectacled, and would rub his temple with the inside of his wrist, asserting that he had only ever had the best of intentions, but now he was forced to admit how misguided, indeed, how disastrously damaging his cruel regimen had been (as had, for example, his use of a fishing rod as an instrument of chastisement).

Illuminating this fiction in his mind had filled the boy with such blissful shudders that he tore his pants down and began to rub his lower body against the tree bark in ever more vigorous motions, and when he then imagined his parents culling his skeletal remains from the ashes with chopsticks, a meager and unfortunately all too brief spray of sparks shot off behind his eyes, somewhere in his brain’s nucleus accumbens, and the boy ejaculated, fluidlessly and softly panting, on the linden tree.

His knees shaky, he staggered back to his oblivious parents (his mother usually awoke from her afternoon nap at this moment), who now invited him to take part in their beloved family ritual: lying in the autumn leaves, their mushroom baskets beside them, and reading aloud from the poems of Heinrich Heine, which his father, an emeritus professor of German at Tohoku University, had strained to translate into Japanese and now, under the influence of two or three savored beers that lubricated his voice, was declaiming heavenward in the original German, not without humor switching the R with the L in his delivery. Oh, how Masahiko hated his father!

Masahiko had of course taught himself the German language long ago, and now he inwardly squirmed and writhed at the merely half-feigned speech impediments of his father, who, while inevitably proud of his son’s genius, at the same time felt an extraordinary unease about it; Masahiko seemed intensely creepy to him, much as the deep sea and the blindly groping leviathan reputed to lurk down there in its eternal dark might terrify anyone.

His son, who at not quite nine years of age had mastered seven languages, and who was in the process of teaching himself Sanskrit, who, smiling shyly, would write down complex algorithms while masticating his breakfast rice, would compose brooding concerti on their piano at home, and would read Heine in German, seemed to his father possessed by a merciless demon forcing the child into an ever more grotesque thirst for knowledge. Some parents might wish for such a talented child, whereas Masahiko only filled the Amakasus with horror.

Sometimes they would sit together before a small carton on the floor and gaze at photographs of him as an infant, of his first attempts at walking, of his delighted splashing in the wooden tub or grasping a colorful rubber ball, and then they would feel a thoroughly crushing sadness, as if they were seeking to conjure up in those images that frozen, irretrievable time solely through the power of their longing, as if they sensed their child were being snatched from them most unnaturally.

Related to the feelings of the Ainu, those ancient inhabitants of Japan who sometimes refused to be photographed because they feared that fixing their likeness would rob them of their soul, Masahiko’s parents occasionally felt, conversely, that these likenesses were their true son, and that the boy growing up there beside them was merely a replica, an unreal mirror version, a dread homunculus.

10.

When had his sexuality begun to take wing out of the baser regions of those childish fantasies of repression and death, rising to actual carnality? Early, early indeed; he must have been nine or ten years old, Masahiko.

There had been a governess, whose slende

r, clean forearms, covered in vulpine down, protruded from her violet-checked little dress when she, her tunic hiked up high, had thrown her much-too-skinny stork legs over his as they lay prone together, cheek to cheek, leafing through a picture album that depicted the victory of the Japanese army over the cowardly retreating Soviets in Chinese Mukden. The girl’s breath had smelled of biscuits.

And while he had felt the weight of her legs and the contractions of her muscles, as well as the hopeful, high trembling of the respiratory system connected to them, he had inserted his forefinger into her half-open, moist oral cavity. She, in turn, had called his name softly and whispered: iku!

Thereafter, they had lain together in a tight embrace and listened to the wind, which scratched a twig on the shōji. He had loved her more than he would ever love anyone. Four months later, she died in a rather insignificant automobile accident in Tokyo; the steering column of the vehicle, which she should not have been driving in the first place on account of her youth, had squeezed her against the seat and collapsed her lung; glass rained kaleidoscopically, and blood gushed from her mouth like jelly.

11.

His father had really hit him only once, this was in the face with the back side of his clenched fist; Masahiko bit his fingernails, bit them until there was nothing worthwhile there left to bite, and so the boy soon assaulted his toenails, too. One afternoon, his mother led him to his father’s studio, saying she no longer knew what to do, just look at his toenails, they’re almost entirely gone, completely gnawed off—and the boy had timidly curled his toes toward the floor to hide them as if they were retractable claws, only to receive in the next instant that wholly unexpected wallop, the blunt, drastic vehemence of which sent him hurtling backward and tumbling to the unpolished wooden floor like an unthreaded marionette.

His greater loathing was reserved for his mother, however, because she had delivered him to his fate and then not defended him; while falling he had been able to make out in her face something akin to consenting amazement, her expression contracting in the middle of her furrowed brow—though one might have also read it as astonishment at the severity of both the punishment and the abrupt appearance of his father’s aggression—but as if the pent-up rage at Masahiko’s disconcerting thirst for knowledge had found its natural expression in that backhand, it was clear that she had also secretly welcomed the strike and even endorsed it.

The boy lay whimpering on the ground, the ringing thunderous sound of a bell in his ears; Mr. Amakasu rubbed his throbbing hand. On his desk the small, round pale-violet paper snippets that the paternal hole puncher had spewed out for years to the child’s delight and that, as an infant, he had always placed in his mouth to taste sank imperceptibly deeper into the indentations on the writing surface as if ashamed. The tropical bird over in the aviary, which they had bought as an expression of their unbourgeoisness, had nibbled with disinterest on a cookie.

12.

Whether it was Doctor Nägeli himself or perhaps his wife who had decided to give little Emil a rabbit can no longer really be pieced together. In any case, propped up there in the shed one day outside the windows of the yellow-carpeted playroom was a splendid wooden cage in which the animal sat, face and paws expectantly, almost slyly, directed ahead, staring at Emil, and Emil stared back, spellbound, and gave him the name Sebastian.

Emil had known from children’s books what rabbits liked to eat—if he approached the animal, however, to feed it a carrot, he was bitten fiercely on the fingertip; the child was utterly startled, having been shielded until then in the thought that existence and the world were, in their very essence, civilized. Never before had he experienced the indecent and indiscriminate savagery of nature.

Sebastian had been an intractable white albino with red eyes, and little Emil had loved him with an ardency edged with pain. Thus, without ever being able to approach the animal, the boy cleaned out its cage every couple of days, stuck the tips of his fingers through the wire mesh of the little stall door, was bitten again and again, for hours raptly contemplating the twitching whiskers on the dear pink nose that turned warily toward him, and observed as the soft paws slid food about.

Emil longed to be able to stroke Sebastian’s silky fur, to embrace and pet the animal, bringing him bushels of dandelion leaves he had picked in the meadows, yet there was no opportunity for rapprochement, only the perhaps naïve thought that if he treated the rabbit lovingly it would one day love him in turn.

The rabbit stall emitted the deplorable and sharp reek of the animal’s acridly pungent feces. The little dark-green pressed food pellets that his mother would bring home in brown paper bags and that he would stick in his mouth to sample tasted vaguely like rubber.

Sebastian ate them anyway; delicate, fresh dandelion or mass-produced feed, it was all the same to the rabbit. Once the neighbor’s cat crept into his parents’ garden, and Emil opened the stall door so that his Sebastian would have someone to play with. The rabbit, however, chased after the intruder across the lawn, hissing murderous snarls, its fur puffed up on end, and the cat vanished in panicked fear.

That small, pointed, nerbling rabbit mouth was now appearing to the boy every night in his dreams; but when he tried to wake up, he would tumble out of bed and then lie there on the floor in the hopeless darkness of the nursery, crying for help, incapable of distinguishing up from down and left from right; this confusion was so primordial that even his mother—after running from her bedroom two floors up on account of her child’s shrieks, seizing and shaking the wailing Emil, turning on the lights, and imparting to him words of reassurance and comfort—was incapable of allaying her hollering son’s inexorable, screaming disorientation for quite some time.

He felt as if his mother weren’t able to reach him, as if he were floating underwater, shackled forever in the half sleep of that nightmare, and his mother were standing on the other side of a membrane that imprisoned him, calling and caressing him from without, but that there was no way for him ever to reach the other side.

How childish that had been. Luminous day had hardly materialized, the room’s green-plaid curtains had scarcely been torn open, and the familiar garden and the attendant shadows of the firs tremulously projected by that curative camera obscura onto his childhood wallpaper—where the pleasingly repeated arrays of branches and cherry blossoms validated the soothing panorama of his innocent horizon of experience—when the fears faded away, warded off by the genial light of morning. The witches under his bed withdrew and did not dare emerge again during the day.

Lying recumbent on his parents’ silken sofa that afternoon, Emil had stuffed a pillow under his neck and lost himself for hours in the cloud formations developing in the sky outside the window, had drifted off to sleep, waking up seconds later, six hours later, and in this intermediate world he learned of his special gift to curse someone just one single time in life and to have this curse come true one hundred percent.

While lying there, he had also spotted a very special tree a decent distance away that he would see time and again during his life; he discovered it not only in Switzerland, but also on the Baltic coast of Germany, in Italian Somaliland, in Japan, and in Siberia, and only much later, in the latter third of his life, did he realize, this time while astride a toilet, that this would be the tree he would see at the moment of his death, not in benightedness like his father, but clearly and happily, and in full consciousness.

When he returned home early one day from a school field trip the children had taken to the caves of Saint Beatus on Lake Thun—according to legend a place where the eremitic monk had driven a red dragon down into the water with ceaseless, shouted prayers—he found Sebastian’s cage empty.

Weeping, Emil ran through the yard, calling for his rabbit, scouring the house first, then the little street that intersected a busier one at the curve, and when he began to make leaflets with a hastily but nonetheless carefully drawn rabbit on them to distribute throughout the neighborhood, his mother appeared and told hi

m in a quiet voice that Doctor Nägeli had seized the rabbit by its ears and given it to the neighbors, a crude farming family, who that same day had killed the animal and flayed the white fur from it, and what’s the matter? The rabbit had only ever bitten him anyway, he hadn’t been able to play with him or feed him, it was better this way, and Emil really oughtn’t look so crestfallen.

Nägeli was seated on the train. The memory of Sebastian into which he had fallen had not even lasted a second. He shot up—while, outside, a nondescript vernal landscape drew past—and suddenly he again heard his mother telling him via telephone (the connection oddly cushioning her voice) that his great-aunt was still locked outside and she was coughing so loudly and no one could endure the noise. In winter and summer alike they had forced his aunt to sleep in the barn—presumably it was whooping cough or tuberculosis—and at some point this aunt had of course slashed her throat with a straight razor because she was so lonely.

But how can anyone possibly live with something like that, he had asked his mother over the telephone, and he was told that’s just how it was. Sometimes his throat seemed to close up when he reflected upon the remorselessness and brutality of his family.

13.

Many months later, after he had already been in Japan for some time, and following an exhilarating but also thoroughly exhausting hike that led him first past green-budding rice terraces, then over desolate, darkly desaturated hills, Nägeli came upon a wooden hut at the end of a gently ascending path that nature seemed to have reclaimed. The structure’s situation in the landscape elicited in him a profound sense of absolute harmony and proportion.

Pine forests yielded to placidly jagged ridges, the half-concealed foothills of which trailed off into infinitude, into a haziness caused by ground fog, as if they had been cut from translucent colored paper. The hut, which now lay at some distance before and slightly below him, seemed so very fragile, its earthen foundation having been erected in an almost makeshift fashion.

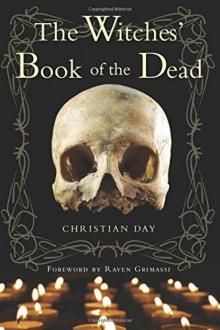

The Witches' Book of the Dead

The Witches' Book of the Dead